Tax-efficient and financing-efficient UK individual investing

In my last post I gave an example of a situation where individual investors might want to borrow money for investment purposes. This post will give an overview of the methods that individuals can use to achieve that leverage efficiently. I will also cover tax considerations, some of which may be relevant even to unleveraged positions. Much of what I cover here will be UK specific, particularly when it comes to taxes.

Before we begin I should probably say that I’m not a tax accountant, a lawyer, a professional financial advisor, or anything else: I’m just a guy with access to Google and an interest in efficiency. You should probably speak to a professional before acting on any on the info in this article! I do work for an investment company, but I’m certainly not speaking for them here, and the information in this post has little-to-no relevance to their business. This is simply a summary of my understanding based on my research – I haven’t actually tried most of these methods in practice. I would appreciate feedback if you notice any errors.

Secured Lending

A secured loan such as a mortage or HELOC is the form of borrowing that is probably most familiar to people. Because these loans are backed by an asset (i.e. probably your house), you can get very good interest rates: I see 2 year fixed teaser rates as low as 1.2% AER, which is less than 1% above the overnight GBP LIBOR rate of 0.225%.

The obvious downside of this form of borrowing is that the amount you can borrow is limited by the amount of home equity you have.

Margin

Many stock brokerages offer margin accounts to their customers. A margin account is one where you are allowed to borrow to invest more than you have deposited into the account. The borrowed capital is secured by the equity in the account, which must meet a minimum value threshold (“margin requirement”), normally defined as some fraction of the total notional value of the account.

The broker I’m most familiar with is Interactive Brokers (IB). Roughly speaking, their rules allow a margin account to borrow up to 100% of the value of the equity in the account (i.e. achieve 2x leverage). The interest rates charged are fairly low: right now, for GBP borrowing they charge 1.5% above LIBOR. The rates get more competitive if you borrow more – loans above GBP 80,000 only attract a charge of 1% over LIBOR.

If you’re using a broker’s margin facility you obviously need to accept their schedule of trading costs too. Luckily, IB’s fees are just as competitive as their margin charges, and start at around 6 GBP for an equity trade.

Futures

If you want to invest in an asset on which a liquid futures contract exists, this can be a very cheap way to achieve leverage. At the time of writing, a single FTSE 100 index future contract has face value of around 73,000 GBP. The returns on this contract will closely match the returns on investing that same face value in an index tracking ETF. However, unlike with an ETF investment, if you purchase one of these futures contracts, you don’t need to invest those tens of thousands of pounds upfront – instead, you just need to deposit a certain amount of margin with your broker. Right now, IB only require about 6,500 GBP of deposited margin for a FTSE position held overnight, so you can potentially achieve 10x leverage without paying any financing costs.

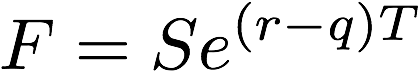

If you use futures to make long-term investments in assets it is important to understand how the returns you earn on futures differs from that on the underlying asset. By an arbitrage argument you can show that the price of a futures contract should be equal to the forward price F:

Where S is the spot price of the underlying instrument (in our example, this would be the FTSE 100 index), T is the time to expiry of the contract, r is the risk-free rate and q is the “cost of carry”. The cost of carry is essentially a measure of the return you earn just by holding a position in the underlying. For an equity index future like the FTSE the cost of carry will be positive because by holding the components of the FTSE you actually earn dividends. For commodity futures the cost of carry may be negative because you will actually have to pay to store your oil or whatever.

If the spot price of the underlying stays unchanged, the daily return R on the contract will be:

This illustrates the key difference between holding the underlying and the future. With the future, you don’t just earn the returns of the underlying asset. – the value of your contract also decays each day by an amount related to the difference between the cost of carry and the risk free rate. If this decay costs you money, the future is said to be in “contango”, otherwise it is in “backwardation”. You can somewhat offset the decay due to the risk free rate part of this by depositing the notional amount of your investment in an account that earns the risk free rate. However, even if you do this, you wouldn’t expect the returns on your position to perfectly match those of the ETF because the forward price is determined based on the expected risk free rate and cost of carry. If interest rates are unexpectedly low, or dividend payouts are unexpectedly high, then your futures investment will underperform the equivalent ETF, so you are bearing some additional risk with the futures investment.

The other issue with futures contracts is that if you hold them for the long term you will need to deal with the fact that they have a limited lifespan. For example, the June 2017 FTSE 100 contract expires on the 16th of June. On or before that date you will need to sell your position in the June contract and buy an equivalent one in a later one (e.g. the September 2017) contract, or else you’ll stop earning any returns from the 17th June onwards. This regular roll process incurs transaction costs which acts as a drag on your investment. Thankfully, futures contracts are generally very cheap to trade: not only does the bid-ask spread tend to be tight, but brokerage fees are lower – IB only charge GBP 1.70 per contract to trade FTSE 100 futures, and most futures have extremely tight bid-ask spreads that are essentially negligible from the perspective of a long term investor.

One problem that makes index future investment particularly tricky for the individual investor is that these contracts generally have rather large notional value. The ~70k GBP value of one FTSE contract mentioned above is quite typical. So if you only have a small account, you can’t really use futures unless you’re willing to accept enormous leverage and all the risks that entails.

Contracts For Difference

Contracts For Difference (CFDs) are an instrument you can buy from a counterparty who specialises in them. Big UK names in this area are IG, CityIndex and CMC Markets, though IB also offers them. Like a futures contract, these products let you earn the returns on a big notional investment in an asset without putting down the full amount of that investment upfront – instead, you just need to deposit some margin. Depending on the provider and the reference asset, the margin requirements can be very low: CityIndex seems to only require 0.5% margin for a UK index investment, allowing for a frankly crazy 200x level of leverage. IB only require 5% margin.

Also like a future, CFDs are not available on just any underlying. It’s easy to bet on equity indexes, FX, and big-cap stocks with CFDs. It is also reasonably common to find bond or commodity CFDs, but not all providers will offer a full range here (IB don’t offer any). The other characteristic that CFDs share with futures is low trading costs: for index CFDs, providers commonly only charge a spread of 1 index point, i.e. about 0.01% for the FTSE 100. IB as usual offer a good price of only 0.005% per trade for version of the FTSE 100.

Now we turn to the differences between CFDs and futures. For starters, unlike futures, CFDs do have financing costs, and they are chunky: typical rates from CityIndex and friends are 2%-2.5% above LIBOR, with IB again offering an usually good deal by only charging a 1.5% spread. On the plus side, if you hold a position in an asset via a CFD you will recieve dividends on that underlying, something that is not true if using a future.

Spread Bets

Spread bets are a bit of a UK specific way to lever yourself up. Many companies offering CFDs in the UK also offer spread bets. These are essentially CFDs in all but name, and will face almost identical trading and financing costs as compared to the equivalent CFD product. They are also generally available on exactly the same set of underlyings. The key difference between a CFD and a spread bet is that spread bets are treated as gambling rather than investing by the tax system, with the consequence that earnings via one of these instruments are subject to neither capital gains nor income tax!

I will return to the issue of tax later, as there is quite a lot to say on the topic.

Options

Options are a slightly more complex way to gain leverage than the above alternatives. The idea here is that if you want to make a leveraged long bet on e.g. the FTSE, you can achieve that by buying a long-dated call option with a strike price somewhere around the current level of the index. Because the strike price is high, you will be able to purchase the option relatively cheaply, but you can potentially recieve a very high return. For example, let’s say the FTSE is around 7000: you might be able to buy an option on 1x the index expiring in two years with a strike of 7000 for around 400 GBP. If the index is up 10% to 7700 at that time, then you will earn a profit of 700-400 = 300 GBP i.e. a 75% return on your investment, so you have effectively have 7.5x leverage.

Like futures or CFDs, options are only available on certain underlying assets. In the US, you can buy options on equity indexes with expiries up to three years in the future: these are known as LEAPs. Exchange-traded options with long expiries are also available in other countries: for example, the ICE lists FTSE 100 options expiring a couple of years ahead.

Also like with futures, investments via options won’t earn any dividends, but neither will they attract financing charges. Individual investors may have difficulty with the fact that these options have notional values in excess of 50,000 GBP (in the US, S&P 500 mini options with smaller notionals are available, but they only list about 1 year out).

There are two other ways of purchasing options that may be more suitable for the UK small investor as they let you take a position in a smaller size. Firstly, companies offering spread bets tend to also sell options. I haven’t looked into this, but given how expensive their spread bet financing is, I would not be surprised if their options were substantially overpriced. Secondly, you can purchase a “covered warrant”, which is essentially an exchange-listed option targeted at individual investors. Societe Generale offers them via the London Stock Exchange: i.e. these options can be purchased just like a regular stock.

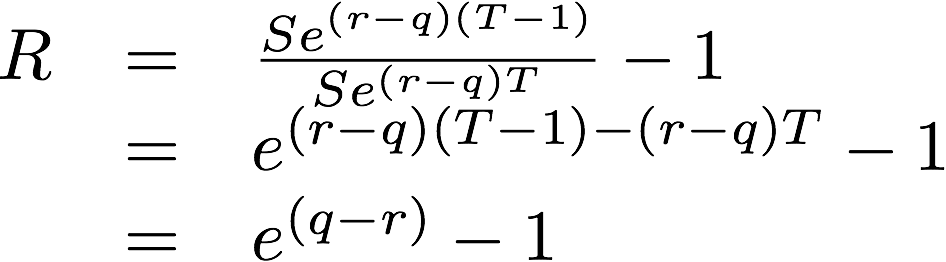

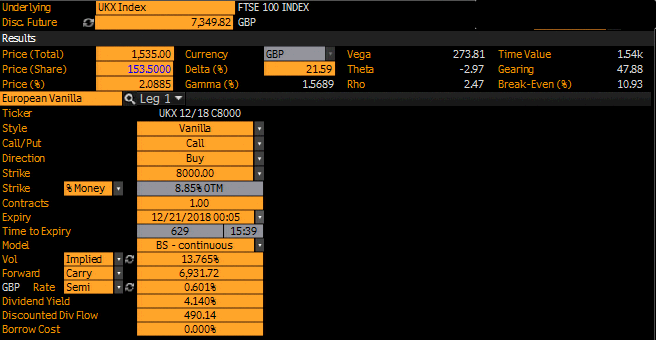

I did have a brief look into whether covered warrants offered good value for money. Specifically, I looked into the cost of SE91, a call option on the FTSE 100 with strike price 8000 and expiry December 2018 (the longest dated option available at the time of writing). When I looked at it, the warrant was quoting at around 0.25 GBP with a spread of 0.002 GBP (1%):

The equivalent exchange-traded option was had a mid price of about 156 GBP on a spread of about 50 GBP (32%):

The exchange-traded option is for a notional exposure 1000x larger than the warrant, which explains the order-of-magnitude difference between the prices. Taking this into account, the warrant looks pretty expensive, with even the bid price of 0.2488 GBP being higher than the equivalent exchange-traded option ask of 0.1805 GBP.

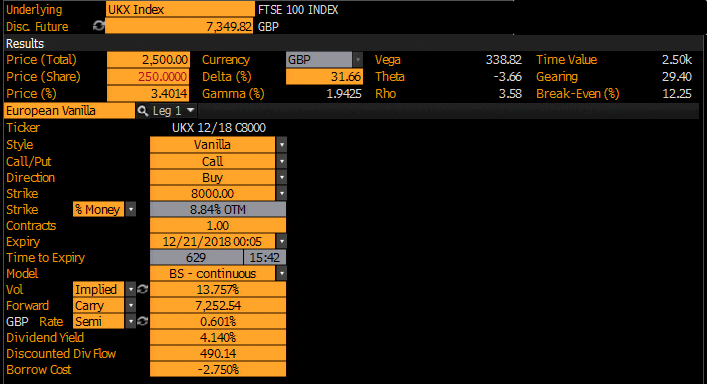

We can quantify exactly how much more expensive the warrant is by using the Black-Scholes option valuation model. Given the level and volatility of the FTSE at the time, the model implies a fair market value for the option of 153 GBP, which lies within the bid-ask spread we actually observe on the exchange:

SocGen are trying to charge us about 250 GBP for equivalent exposure. To put this in the same terms as the financing costs for the other instruments (i.e. as a spread to LIBOR), we can tweak the borrow cost assumption in this model until we get the right price out:

So it looks like the SocGen options are effectively offering leverage at a cost of LIBOR plus 2.75%, which is not a good deal. Trading them might still make sense so long as you are intending to hold them short-term, because they have much narrower bid-ask spreads than the exchange-traded equivalent, but in this case you’d probably end up better off buying the options OTC from a spread betting company.

I won’t consider options further as frankly speaking I find them harder to analyse than the alternatives.

UK Taxes On Investments

There are four forms of tax that are relevant to investors operating in the UK:

- Stamp duty: payable upon purchasing an asset

- Dividend tax: payable upon recieving dividends from an asset

- Income tax: payable upon recieving non-dividend income from an asset

- Capital gains tax: payable upon sale of an asset

Stamp duty is the simplest of the three. It’s a flat 0.5% charge upon the purchase of shares in individual companies. It is not payable on the purchase of ETFs, futures contracts, or spread bets, so mostly not very relevant.

The amount of dividend tax you pay depends on your total income in a year, and can range from 0% (if your dividends amount to less than the current tax-free allowance of 5,000 GBP) to 38.1% (if you pay “additional rate” tax of 45% on income above 150,000 GBP).

Income tax is payable on income from an asset that is not considered to be a dividend. Basically, if the asset is a bond, or a fund more than 60% invested in bonds, you will have to pay income tax instead of dividend tax. Income tax can range from 0% (if you earn less than the current Personal Allowance of 11,500 GBP) to 60% (if the income from dividends pushes you into the 100,000 GBP to 123,000 GBP band where the Personal Allowance is withdrawn). For more info see HMRC and this discussion of the marginal tax rate. It’s not 100% clear to me what the tax treatment is on the final repayment of principal made by a bond issuer. I suspect the final repayment is treated as a capital gain, and for UK government debt at least it seems that no capital gains tax is payable.

Capital gains tax is payable on realised gains in excess of the annual 11,300 GBP threshold. Higher rate taxpayers (i.e. those earning above 45,000 GBP) will pay 20% on anything above this. Those who don’t pay higher rate tax may only pay 10% on some amount of their gains.

Capital gains tax is perhaps the trickiest of the taxes. Firstly, you need to know that it’s calculated based on your net realized loss during a year. So if you make a gain by selling some asset, you can avoid paying tax on that by selling another asset on which you have booked a loss. If you realise a net loss during a year, that can be carried forward indefinitely to be set against future capital gains.

Secondly, note that that the tax free amount of 11,300 GBP is a “use it or lose it” proposition: if you don’t have 11,300 GBP of gains to report in a year then you won’t be able to make use of it, and it will vanish forever. This ends up being another reason to invest in a diversified portfolio of assets: if you are diversified then you’re likely to have some asset that you can liquidate during a tax year to take advantage of the allowance (just be careful that you don’t fall foul of the “bed and breakfasting” rules – see this guide to realizing capital gains for more info).

One general theme of all this is that you generally end up paying less tax on capital appreciation than on dividends.

Tax Efficient Investing

For concreteness, let’s say we are interested in making a (either leveraged or unleveraged) investment in equity indexes. How do these taxes apply to the investing methods discussed above, i.e. ETFs, futures, CFDs and spread bets? As already mentioned, none of these assets attract stamp duty. But what about dividend and capital gains tax?

ETFs are relatively straightforward: you pay dividend tax on the distributions, and capital gains tax upon selling an ETF that has increased in value. This may mean that it is more tax efficient to purchase an ETF that reinvests divends for you (like CUKX) rather than one that distributes them (such as ISF).

Futures contracts are straightforward: there are no dividends, so you simply pay capital gains tax. One potential problem is that you won’t have much control over when you realise gains for capital gains purposes because you’ll probably be rolling the contracts quarterly anyway. Furthermore, if you have taken that portion of your equity that does not go towards the margin requirement, and invested it in an interest-bearing account, then you will have to pay income tax on any interest income. For tax purposes it might be most efficient to invest in a zero-coupon government bond which will not attract either income tax or capital gains tax, but this might be more trouble than it is worth.

The tax treatment of CFDs is interesting. All cashflows due to the CFD are considered to be capital gains by HMRC – what’s surprising is that this this includes both the interest you pay to support the position, and any payments you receive as a result of the underlying making a dividend payment. This makes CFDs rather attractive: you can end up paying capital gains tax rates on dividend income, and benefit from being able to use you interest payments to reduce capital gains liability, reducing the effective cost of margin by up to 20%.

Finally we come to spread bets: as mentioned earlier, bets are subject to different rules, so you don’t pay any tax at all on these. The flip side to this is if of course that if you make a loss, you aren’t able to offset it against capital gains elsewhere. It’s not totally clear to me whether this treatment applies to payments made on the spread bet as a result of dividend adjustment, but it looks like it may do. This is why some spread betting providers (e.g. CoreSpreads) only pay out 80% or 90% of the value of any dividend to the punter. One last thing to note is that the spread betting providers themselves pay a betting duty of 3% on the difference between punter’s losses and profits: this will of course be passed on to you in the form of higher fees.

Summary

This is a lot of info to take in, so I’ve tried to summarize the most important points below. Trading costs assume a 100,000 GBP investment in the FTSE 100.

| Secured Lending | Margin | Futures | CFDs | Spread Bets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available underlying | Anything | Anything | Equity indexes, debt, commodities, FX, certain equities (though liquidity may be limited) | Equity indexes, debt (sometimes), commodities (sometimes), FX, certain equities | |

| Approximate max leverage | 4x (assuming 75% LTV) | 2x | 10x | 200x | 200x |

| Financing cost above LIBOR | 1% | 1% to 1.5% | 0% | 1.5% to 2.5% (20% less if treatable as capital loss) | 2% to 2.5% |

| Other holding costs | 0.09% (Vanguard's VUKE ongoing charge) | 0.014% (quarterly roll costs) | 0% | ||

| Trading costs (FTSE 100) | 0.09% (VUKE 0.06% bid-ask spread, 0.03% commission) | 0.0017% | 0.005% | 0.01% | |

| Dividend treatment | Paid in full by ETF provider | None, but expected dividends become a positive carry on holding the contract | Paid in full | Generally paid in full but some providers may withhold 10%-20% | |

A return-boosting idea

As a final note, here’s something I just noticed and haven’t seen mentioned anywhere else. If investing via a CFD, spread bet or futures contract, you only need to deposit margin with your broker. If you’re only using 1x leverage, this means that 90% of the notional value of your investment is free for use elsewhere, so long as you are able to move it back to the margin account if needed.

What’s interesting is that as an individual investor it’s straightforward to find bank accounts that pay more than the risk free rate – even though these accounts do enjoy full backing from a sovereign government, and so are risk free in practice. For example, right now I can see an easy-access (aka demand deposit) account from RCI Bank accruing interest daily and paying an AER of 1.1% on balances up to 1 million pounds – i.e. about 0.9% above LIBOR. This is higher than the financing cost of a futures position (though not a CFD or spread bet), so it seems to me that there is reason to believe that the returns on a futures investment will actually beat out the equivalent ETF, so long as you do invest the “spare” equity in this way.