FizzBuzzing At The Type Level

It seems like the FizzBuzz meme has resurfaced, thanks to this reply to Raganwald’s post on the subject. Since I didn’t get on the bandwagon last time, I thought I’d take a crack at implementing with a bit of a twist: using the Haskell type system! This is my first moderately large type level program, so it’s probably not quite as elegant as it could be, but it does work and is fairly readable.

As you may know, the FizzBuzz task is to output a list of length 100 that contains a “fizz” whenever the associated index is divisible by 3, a “buzz” if it is divisible by 5, and the concatenation of the two if the index satisfies both of those conditions.

Let’s take a look at how we can build up a monstrous abuse of the GHC type system to implement this specification piece by piece. First, we need to turn on a crapload of options to make the compiler accept the twisted program we are going to give it:

{-# OPTIONS_GHC -XEmptyDataDecls -XMultiParamTypeClasses -XFlexibleInstances -XFunctionalDependencies

-XTypeOperators -fallow-undecidable-instances -fcontext-stack=200 #-}Now, we need some notion of numbers in the type system so we can actually compute divisibility. The standard trick here is to use the Peano numerals, and since it’s quite a common need there are actually existing libraries for this: for instance, I could use Oleg’s amazing code that even does things like type level logarithm and factorial. However I want the example to be self contained so I will just implement the restricted arithmetic system that I need for FizzBuzz here:

module Main where

data S a

data Z

type Zero = Z

type One = S Z

type Three = S (S (S Z))

type Five = S (S (S (S (S Z))))

type OneHundred = (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S

(S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S (S Z)

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))That’s all very well, but we also need to be able to do operations on these numbers at the type level. To do this, we encode type level functions as type classes with associated instance declarations: one for each recursive case. We also mix is some magic pixie dust by using appropriate functional dependencies to make sure that we restrict the instance to be really functional, rather than relational.

Here’s an example of this, for the subtraction function:

class Sub a b c | a b -> c, c b -> a where

instance Sub a Z a where

instance (Sub a b c) => Sub (S a) (S b) c whereThis definition should not be too surprising to you if you’ve seen Peano arithmetic or Church numerals before: it’s pretty standard recursive style. However, the modulus function is rather more interesting:

class Mod a b c | a b -> c where

instance (ModIter a b b c) => Mod a b c

class ModIter a i b c | a i b -> c where

instance (Sub b Z a) => ModIter Z Z b Z where

instance (Sub b (S i) a) => ModIter Z (S i) b a where

instance (ModIter (S a) b b c) => ModIter (S a) Z b c where

instance (ModIter a i b c) => ModIter (S a) (S i) b c whereEeep! The essential trick here is to use a helper type class, ModIter, to loop repeatedly through the range from the modulus we are using down to 0, where on every iteration we subtract one from the thing we want to find the modular reduction of. When we can no longer decrement that number any further (i.e. it hits zero) we exit the loop. The result is just the modulus minus the current iteration number in the inner loop, which gives us exactly the remainder we need. To help you put this in the context of the definition above, the type variable a is the current number we want the modular reduction of, i is the inner loop index, b is the (constant) modular base and c is the eventual result.

Whew. Not too simple! That’s probably the most complicated bit of the program however, it’s easy going from here on out! First, let’s have some helper functions for computing various mod operations:

class Mod3 a b | a -> b where

instance (Mod a Three b) => Mod3 a b where

class Mod5 a b | a -> b where

instance (Mod a Five b) => Mod5 a b whereNow we get onto the actual business of FizzBuzz: we’re going to need yet more types. We start with some to represent the possible values in our output list:

data Boring

data Fizz

data Buzz

data FizzBuzzOf course, there isn’t really any such thing is as a type level list yet! Let’s have one of those too:

data Nil

data a :+: bGreat. Now, we need to be able to work out the current fizzbuzziness of any particular index. This is pretty straightforward with the following definitions:

class Fizziness a b | a -> b where

instance Fizziness Z Fizz where

instance Fizziness (S a) Boring where

class Buzziness a b | a -> b where

instance Buzziness Z Buzz where

instance Buzziness (S a) Boring where

class FizzBuzziness a b c | a b -> c where

instance FizzBuzziness Boring Boring Boring where

instance FizzBuzziness Boring Buzz Buzz where

instance FizzBuzziness Fizz Boring Fizz where

instance FizzBuzziness Fizz Buzz FizzBuzz where

class AnswerAt i a | i -> a where

instance (Mod3 a m3, Mod5 a m5, Fizziness m3 f, Buzziness m5 b, FizzBuzziness f b o) => AnswerAt a oIt’s all a bit tortured to ensure that we can prove to the compiler that the functional dependency on AnswerAt is respected, but it otherwise quite basic. We have a type class each for both fizziness and buzziness that, given the modular reduction of the index, outputs either the appropriate “noise” type if the mod is 0 (and hence we have divisibility) or the Boring type otherwise. These results are then laboriously munged together by the FizzBuzziness type class in the obvious way, and AnswerAt just serves to tie the knot between all of the components we have defined so far.

Lastly, we can generate the list of results using a trivial (!) type level for loop/map style of thing:

class AnswerIter i a | i -> a where

instance AnswerIter Z Nil where

instance (AnswerIter i a, AnswerAt (S i) f) => AnswerIter (S i) (a :+: f) whereNow, the moment you’ve all been waiting for! Let’s actually get the answer to all our FizzBuzz woes!

tAnswerIter :: AnswerIter i a => i -> a

tAnswerIter = undefined

answer = tAnswerIter (undefined :: OneHundred)Just load this puppy up in GHCi (this may take a while to compile!) and ask for the type of answer:

Prelude Main> :t answer

answer :: (...(Nil :+: Boring) :+: Boring) :+: Fizz) :+: Boring) :+: Buzz)

:+: Fizz) :+: Boring) :+: Boring) :+: Fizz) :+: Buzz) :+: Boring)

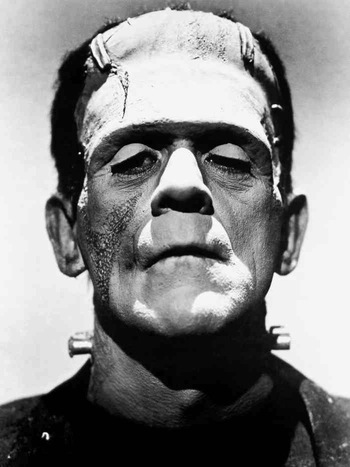

:+: Fizz) :+: Boring) :+: Boring) :+: FizzBuzz) :+: ...)IT LIVES!

Come on, using 100 applications of S is not pretty. How about

In my opinion

instance (Sub b Z a) => ModIter Z Z b Z where

should be

instance ModIter Z Z b Z where

as for i=0 there is no subtraction required for concluding that (b-i) mod b = 0. This is also demonstrated by the fact that the subtraction result 'a' is never used in ModIter Z Z b Z.

FizzBuzz makes a nice example half way from trivial 'natural numbers in the type system' to complicated 'enforce balanced trees with the type system' problems. Thank you!

Get back to work/lectures/sleeping/getting pissed young man. Where will this functional obsession end? It will surely come to no good ;-)